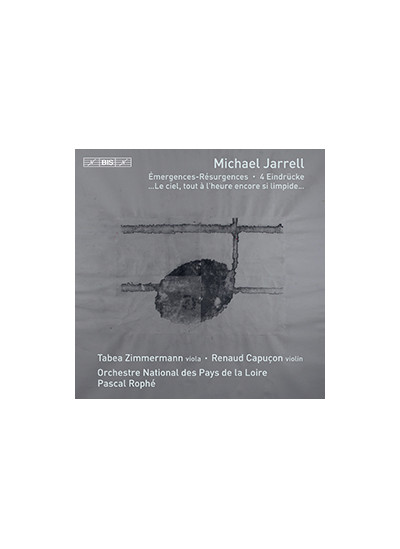

...Le ciel, tout à l'heure encore si limpide, soudain se trouble horriblement...

Play

a sample

20/04/2009 - Geneve, Victoria Hall - Orchestre de la Suisse Romande, Marek Janowski (conductor)

...Le ciel, tout à l'heure encore si limpide, soudain se trouble horriblement...

(...The sky, recently so clear, suddenly becomes horribly murky...)

On the nature... of musicality

Michael Jarrell, born in 1958, is one of the most visible composers of his generation. In his thoroughly personal approach, unaligned with any other movement and relentlessly pursuing an inner quest, he has implemented a synthesis from the legacy of post-war music, extracting various technical features and putting them at the service of true musical poetics. Actually, in contrast with his predecessors, he explores language less as such, making these new techniques the focus for a mutation of musical reflection, rather than trying to subjugate it to expression. He is also wary of excessive conceptualization, and of the utopia that a work could convey, preferring to highlight the virtues of a craft that he teaches in Vienna and Geneva, as well as numerous European seminars. His works, readily distinguishable among the profuse output of contemporary music, are all interrelated, not only by a certain form of sensitivity and their particular tone, but also by the recurrence of particular features that Jarrell reworks in different contexts. Thus, early on, he constituted a universe that he continues to reorganize, aiming less for the seeming originality of each piece than for a constant displacement of perspectives in which the same ideas can in themselves be discerned. "Craft a hundred times over..." this is what could be his motto. We thus discover something familiar in each of his works that at the same time takes on a certain strangeness, a feeling that perhaps constitutes an essential element of his expressiveness. Jarrell's music contemplates territories of dream and unreality, searching for that moment of truth often set in the lowest and slowest sonorities, a place where time, agitated elsewhere, becomes immobilised. It is perhaps this that endows his music with a sort of tenderness inseparable from sonic beauty, even reaching a refined aestheticism, distant from intense research and authoritarian formulae. For him, even the most unusual instrumental techniques, or the electronic sounds that he often uses, are repatriated into a sensitive world derived from purity, where expressive qualities dominate. These do not necessarily refer back to the "me" of the composer, which tends on the contrary to diminish, but rather to the real essence of musicality, to the phenomenon itself, emissary of a singular presence to the world.

The same qualities found in his last work, ...Le ciel, tout à l'heure encore si limpide, soudain se trouble horriblement..., a commission from the Orchestre de la Suisse Romande. It employs a standard large symphony orchestra: 3 flutes (including alto and piccolo), 2 oboes and English horn, 2 clarinets and bass clarinet, 2 bassoons and contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, harp, tympani, 4 percussionists (vibraphone, glockenspiel, tubular bells, cymbals, bongos, tam-tam, bass drum, temple blocks, low tom, spring coils, triangle, mark tree) and strings. Despite a title that could imply a programmatic leaning, the work belongs to the category of pure music. The orchestra is treated in a conventional manner, but with a virtuosic writing style and sonic refinement extremely demanding for performers. Through-composed, the work can be divided into four principal sections of unequal length, the first two being longer than the two that follow: the first consists of a continuum of rapid notes distributed between the strings and the woodwinds, while the trumpets, doubled by various instruments, let loose an incisive calling figure that lengthens progressively. The writing is highly virtuosic, figures in demisemiquavers move from one instrument or from one group to another. The rapid notes come to a halt the first time within oscillations played notably by the divided strings, then during repeated notes that move through the entire orchestral texture. After an intermediary passage favouring low sounds, the animated writing resumes, reaching a dramatic highpoint setoff by trills that is immediately followed by a disintegration leading to the second section.

This section begins with fifths played by the low strings divided and coloured by the percussion (the double basses must be retuned, and play harmonics). The music seems determined to return to a primeval point - it reinvents itself from a basic structure, in extreme gentleness. The impetuosity of the opening gives way to highly refined sonorities. This is a characteristic found in many of Jarrell's works: after the effervescence of brilliant, agitated, nervous writing style that carries the listener along its wild journey, comes a reflective and profound moment, necessitating a reorientation in the way of listening, a plunge into the very nature of the sonic phenomenon. The substructure that unfolds in a slow tempo thus offers another image of the orchestral sonority, as if primordial music, in litany style, were suddenly revealed beneath the brilliant opening layer. It gives the impression of having begun well before the instant it appears, as though rising from deep layers of consciousness, from archaic memory. Moreover, Jarrell redevelops a passage from a previous piece, Music for a While, repossessing its basic material. The impression of depth is due to an extraordinary slowing of time, suddenly producing weightlessness, but also due to a spiral form that contrasts with the directional music that precedes it. The effect provoked by the tangible distance between such contrasts is dreamlike: we no longer know whether the first section, which evades us by projecting itself forward, were nothing but an illusory form, or if during the slow section, we enter into a sort of daydream.

A central passage in this second section is structured around garlands of resonant harp and bell sounds that are completed by suave sonorities played by the entire orchestra. The descending woodwind arpeggios doubled by string pizzicatos that pierce the repeated horn and trumpet notes, in an even gentler ambience, announce the revival of frenetic movement. This time however, it consists less of whirling figures moving through the orchestra than blocks of notes played by the instrumental mass: figures soaring upward that, as a sort of antiphony, are transformed into repeated notes and lead to a peak of intensity. Subsequently, much as a coda, a fourth section arrives at a languishing end: the harmony freezes, polyrhythms cancel all sense of meter, long held notes in the low instruments descend chromatically while the percussion plays ritual figures, in resonance, until final stillness.

The title of the piece is taken from Lucretius (On the Nature of Things). It does not have an immediate structural significance, as often is the case for Jarrell, but expresses in several words the idea that governs the piece. The murkiness refers to a type of strangeness, to something troublesome that is incongruous in a narrative style, such as stormy wind in a calm sky, but emerges as the very essence of the formal articulation between two styles of writing, two styles of expression that call for opposing temporalities. The suddenness is the reversal between the two. Even so, we once again find an identical nucleus between the lively sections and slower sections, with the fifth playing a structural role in both cases, and the Eb emerging as a pole note (all of Jarrell's music exerts attractions due to poles that orientate listening). If the passage from limpidity to murkiness is rendered by the orchestral sonority, by the highly sensitive manipulation of timbres largely derived from French orchestral tradition, it is also elaborated by figures that elude any thematic profiling, any melodic form in the traditional sense of the term, which makes up the texture. The listener is directly confronted by the sonic material. And, this is through-composed.

The adjective, poetic, comes to mind to define an invention that distances itself as much from illustrative forms as from schematic constructions, and is essentially based on the organisation of notes to the detriment of effects and the noisy sounds of iconoclast gestures. And, in spite of brilliant passages, in spite of the consistently mastered sonic explosions and virtuosic manipulation of the orchestra, these poetics instead reveal a fundamentally intimist character.

Philippe Albèra